By Robert Stern

Bob Rutford was a remarkable leader in many aspects of life, including at UT Dallas and in the Department of Geosciences.

Robert Hoxie Rutford, son of longtime University of Minnesota College of Agriculture faculty member Skuli Rutford, grew up in St. Anthony Park next to the St. Paul campus. His family is of Icelandic descent.

Bob delivered newspapers in the neighborhood, played football quarterback and was all-city, and ran track at Murray High School. His sports prowess helped him earn a scholarship to the University of Minnesota. Upon graduating from high school in 1950, he enrolled at the University of Minnesota, where he played football as a defensive back and ran hurdles in track all four years, lettering in each sport twice. One week after graduating with a BS in geography in 1954, he married his college sweetheart, Margie Johnson. They were married 65 years and had three children. At the time he died, he and Margie had seven grandchildren.

Bob served in the U.S. Army transportation corps from 1954 to 1957. During his Army service he requested to be transferred to Arctic Services and soon found himself at Thule Air Force Base in Greenland. There he discovered that he was at home on ice. He remained lifelong friends with his Army buddies, and they had regular reunions. Upon completion of his service, he returned to the University of Minnesota for his master’s degree. His thesis research focused on the physical geography of the Sandy and Sachigo Lakes area of northwest Ontario. Progress toward his degree was interrupted, because in 1959, he made the first of his more than 25 trips to Antarctica. Antarctica, his master’s research, and his growing family couldn’t keep him busy enough. He was also head football and track coach at Hamline University in St. Paul from 1958 to 1962.

Investigations of the southernmost continent flourished after the Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959. It stipulated that the continent be used for peaceful purposes, that freedom of scientific investigation continue, and that scientific observations be shared. Funding became available from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) for geologic studies. University of Minnesota geologists under assistant professor Campbell “Cam” Craddock began a series of geologic expeditions to Antarctica. The first, in 1959, included three intrepid souls: expedition leader Craddock, geology graduate student John J. Anderson, and Rutford. Twenty-six-year-old Rutford started working on a geophysical survey to establish the continental margins beneath the sea ice around McMurdo Sound. Snowmobiles were not yet in use, so Bob was his own beast of burden, dragging his equipment on a sled behind him.

The University of Minnesota team returned to the Antarctic in 1960 with five more members. They set up a base camp in the newly named Jones Mountains and began surveying the range. Beginning in 1961, research was aided immensely by using snowmobiles. The 1961–1962 season involved one of the longest traverses by motorized toboggans conducted in the Ellsworth Mountains, then and since, in which both the Sentinel and Heritage ranges were visited. They discovered the key Permian plant fossil Glossopteris, linking the Antarctic mountains to corresponding landmasses in the Gondwanan supercontinent, providing support for the controversial theory of continental drift.

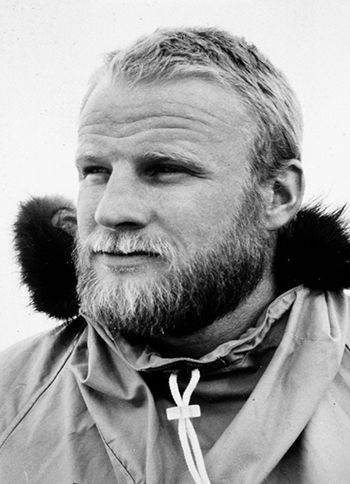

While Bob did complete his MA in geography in 1963, exploring Antarctica was a life-changing experience that prompted him to change his field to geology. He stayed at the University of Minnesota for his PhD research on Antarctic geology under Craddock’s supervision, and was leader of the University of Minnesota Ellsworth Mountains Party in 1963–1964. This work was physically and mentally exhausting, because the team worked inland where they were at the mercy of the weather and the U.S. Navy, who flew the ski-equipped aircraft that got the team around. His dissertation dealt with the glacial geology and geomorphology of the Ellsworth Mountains, the highest mountains in Antarctica.

Antarctica is cold and inhospitable at sea level — can you imagine what conditions are like in its mountains? Camaraderie and leadership must have been critical for survival and success under these conditions, and Bob provided both. You can watch Bob talk about his work in Antarctica in a video that Birkenstock shoes made.

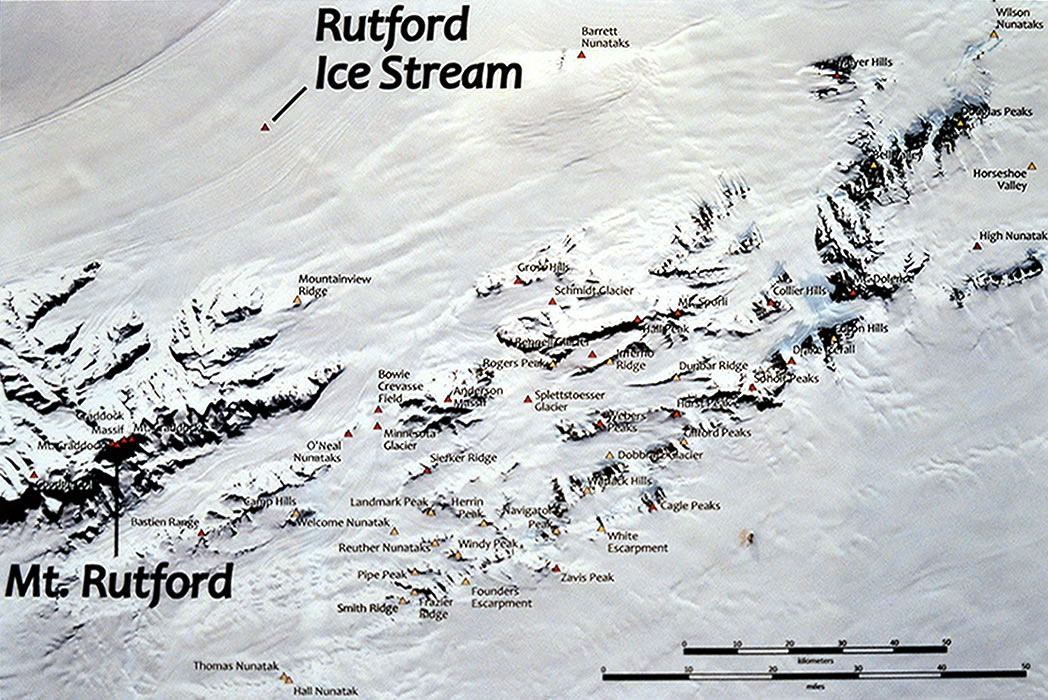

Bob’s last season in Antarctica was in 1995 studying the Royal Society Range and the Dry Valleys. Two important features in Antarctica have been named for him, honoring his leadership in exploring the frozen continent. The 14,688-ft-high Mount Rutford is the summit of Craddock Massif in the Ellsworth Mountains, only 1,500 ft lower than the highest Antarctic peak, the Vinson Massif (16,050 ft). The other is the 180-mile-long, 1-mile-wide Rutford Ice Stream, also in the Ellsworth Mountains, which drains the West Antarctic ice sheet down to the Ronne Ice Shelf adjacent to the Weddell Sea. A map with all of the features in Antarctica named after people from Minnesota (including Bob) or places named by Minnesotans.

Bob’s life can almost be divided in half between Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minnesota (1933–1969), and UT Dallas (1982–2019). In the 12 intervening years, he was moving up the ladder while moving south via posts at the University of South Dakota, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and the National Science Foundation in Washington, D.C.

In 1967, Bob moved to the University of South Dakota as an assistant professor, was promoted to associate professor, and became chairman of the Geology Department in 1969, the same year he received his PhD. Becoming head of a university department the same year that someone gets their PhD is very unusual!

In 1972, Bob and his family moved to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln to head the Ross Ice Shelf Project, a multi-institutional, international Antarctic research project. He also helped establish the Polar Ice Coring Office there, a group focused on ice drilling in both polar regions.

In April 1975, Bob became director of the Division of Polar Programs at the National Science Foundation, overseeing research in both the Arctic and the Antarctic. While at the NSF, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, NSF’s highest award. While in Washington, Bob started his involvement with Zumberge’s Laboratory Manual for Physical Geology, written for freshman-level laboratory courses in physical geology. Jim Zumberge wrote the first edition in 1950, and the last (16th) edition was published in 2014; Bob was involved in 10 of these. According to McGraw-Hill, more than a quarter million students have used this manual.

Bob stayed connected with Antarctic research for more than 50 years. He attended every Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR) meeting from 1970 to 2004 and was the U.S. delegate to Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (1986–2004), its vice-president (1996–98), and its president (1998–2002). As SCAR president he was an effective advocate for scientific research in the Antarctic and for the role of SCAR as the preeminent scientific advisor to the Antarctic Treaty. There are many interviews with him about his Antarctic research and service that can be found on the internet.

The Rutfords returned to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in 1977, where Bob served as vice chancellor for Research and Graduate Studies and professor of geology. In August 1980, he became interim chancellor of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, serving until May 1981.

Bob became UTD’s second president in 1982. UTD then was 13 years old, a fledgling university on the north side of Dallas. UTD began in 1961 as the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest and the first building was constructed on former cotton fields in 1964. Bob served as president for 12 years.

When he took over, the Texas legislature forbade UT Dallas from two important things: (1) enrolling freshman and sophomore students, and (2) teaching engineering. During his tenure as the university’s second president, Rutford helped transform UTD by adding freshman and sophomore students in 1990 and developing the first on-campus student housing. Rutford also provided direction and support for the founding of the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science. There were 7,376 students enrolled when Bob became president in 1982; as of 2019 there are 29,543 students, and UTD is the fastest-growing public doctoral institution in Texas and the second-fastest growing public doctoral institution in the United States. The changes Bob was able to make as president set the stage for this remarkable growth. You can listen or read about these in an interview recorded in 2009. .

He was always busy, but even as president, Bob liked to mingle with UTD faculty and students. He had a big round table built and placed in a corner of the UTD cafeteria where faculty and students would eat lunch, and many days Bob would join us at that table, where he was always welcome.

While at UTD, Rutford bought a home in Jackson, Wyoming, where he and Margie spent most of their summers. Bob was an early member of the Geologists of Jackson Hole (GJH) and served on its board for many years. Each summer, he would give GJH public lectures about his Antarctic research and lead field trips throughout Wyoming and Idaho.

After Bob stepped down as UTD president, he did something very few ex-presidents do: he returned to the classroom. For 13 years after stepping down, he was a professor of Geosciences in our department. He especially enjoyed being around undergraduates and taught courses in introductory geology, which included taking students on field trips.

Bob led by example. He was completely engaged, didn’t mince words, and was never two-faced; he told you what he thought. If you didn’t do your job the way he thought you should do it, he would say so. He never took himself too seriously and never took anyone else too seriously, either. We were sorry to lose him from our faculty when he retired from UTD in 2007 at age 74.

Bob had many awards and recognitions from scientific societies. Bob was a member of the Arctic Institute of North America, Sigma Xi, the Philosophical Society of Texas, and the American Polar Society, and he served on the board of the Geologists of Jackson Hole. He also was a Fellow of the Texas Academy of Science. In 1993, he was elected to the St. Petersburg, Russia, Academy of Engineering, and in 1994 was awarded an honorary doctorate of science from St. Petersburg State Technical University, Russia. The Regents of the University of Minnesota recognized him with their Outstanding Achievement Award and Medal in 1994, and the University of Minnesota “M” Club selected him for their Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995. He holds the Antarctic Service Medal of the United States.

Most recently he was awarded the Medal for International Science Coordination by the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research. He has published numerous articles on Antarctic geology, science, and science policy. He served on the Board of Governors of the American Polar Society. He was a member of the Geological Society of America and was affiliated with GSA’s Quaternary Geology & Geomorphology Division for more than 20 years and was elected Fellow in 1971. He served on the Geology and Public Policy Committee between 1996 and 1998, was a GSA Foundation Trustee and then Chair between 2005 and 2010, when he helped reorganize and refocus the Foundation Board of Trustees and staff.

Bob was a man of quiet and strong faith. His family had Presbyterian roots, but in St. Paul they joined a congregation that they lived next to. As an undergraduate, Bob taught Sunday school to schoolchildren. He would come home from playing football on Saturday afternoons and prepare a lesson for Sunday. When Bob and Margie married, he joined Margie’s Lutheran congregation, and they have remained active in Lutheran churches in every city in which they’ve lived and have supported the ministries of each. After becoming UTD president, Bob and Margie belonged to and supported King of Glory Lutheran Church in Dallas and Shepherd of the Mountain Lutheran Church in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Bob served on the Pastoral Call Committee for the lead pastor of King of Glory Lutheran Church. Each year, Bob and Margie delivered meals on Christmas Day via Dallas Meals on Wheels, and Bob helped build ramps with Texas Ramps to enable those in wheelchairs to have easier access.

Short video about five UTD presidents, including Bob Rutford.

Bob was hospitalized for several months before passing. He told Margie that he wanted to leave something to help future students. His wife this year established the Bob and Margie Rutford Geosciences Fellowship. He and Margie gifted the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics a $100,000 endowment to establish the fellowship as a permanent source of support for geosciences graduate students.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ROBERT HOXIE RUTFORD

1965 (with Craddock, C., Bastien, T.W., and Anderson, J.J.) Glossopteris discovered in West Antarctica: Science, v. 148, no. 3670, p. 634–637, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.148.3670.634.

1966 (with Smith, P.M.) The use of turbine helicopters in United States Antarctic operations, 1961–66: Polar Record, v. 13, no. 84, p. 299–303, https://doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0032247400057272.

1969 The glacial geology and geomorphology of the Ellsworth Mts., West Antarctica [Ph.D. dissertation]: Minneapolis, University of Minnesota, 374 p.